Writing

Hilary Benn and the trouble with audiences

Written by Bridget Christie in The Guardian on December 12th, 2015

Cheering a call to war felt wrong and misjudged – like clapping a triumphant, ludicrously attired matador as a magnificent beast lies needlessly dying

I am a standup comedian, and whether I’m talking about jam or the emancipation of women, my main objective is to make audiences laugh. I don’t necessarily need or want them to agree with me. I’m not trying to persuade them to vote in favour of military action against Islamic State, for example. I’m not asking for their permission to launch missile attacks over Syria, attacks that have the potential to result in the loss of civilian life.

But comedy, like sex or interior design, isn’t an exact science. I don’t have ultimate control over my audience’s responses, and I can’t control how others choose to interpret my material once it’s out there. Sometimes people wilfully misinterpret what I’ve said in order to confirm their preconceived notions of who I am; others attach more meaning to things than was intended. We see what we want to see.

Some people see Jesus’s face on a slice of toast and interpret that as a sign that they should cut down on wheat and gluten; others see it as a sign that the local bakers have invested in a new range of Christian-themed baking stencils. Or that Jesus wants the local bakers to invest in some, so that He doesn’t have to keep making appearances all the time when He has more important things to do.

Some audiences clap and cheer approvingly at the wrong time, or at something you’ve said ironically which they’ve taken at face value. There’s a bit in my current show where I explain what a feminist is, and that “Christmas, birthdays, wallpaper and all music are banned in the feminist community” and “feminists only ever listen to one song, on a loop: kd lang’s Constant Craving”. Sometimes people look genuinely confused and angry at this. The other night, when I said, tongue firmly in cheek, that “I am a feminist. All this means is that I hate all men, both as individuals and collectively…” I got the wrong sort of cheer.

Someone else who got the wrong cheer was Hilary Benn, in the House of Commons last week. The clapping and whooping from MPs following his speech supporting airstrikes in Syria was inappropriate and crass. Someone even audibly shouted “Brilliant!”, as if Benn had been sawn in half, then magically put back together again.

Cheering a call to war felt wrong and misjudged – like clapping a triumphant, ludicrously attired matador as a magnificent beast lies needlessly dying, or a priest who’s just read someone their last rites. What should have been a restrained, sober debate became a celebration of an individual politician’s performance skills. It looked like a House of Commons Live Results Show. I half expected Cameron and Obsorne to hold up cards and shout, “10!”

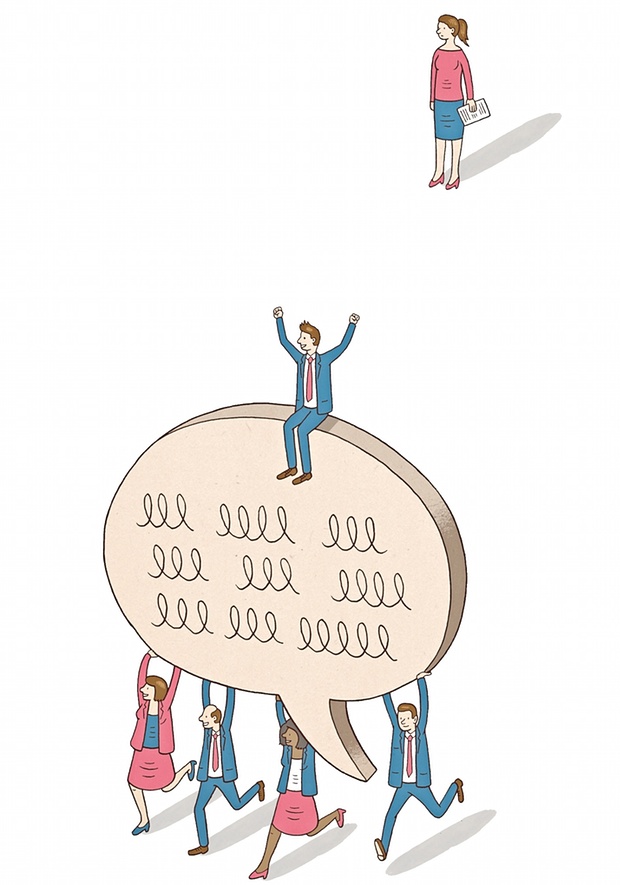

Benn’s speech took on a life of its own. The narrative became about him and his father, the late Tony Benn, former president of the Stop the War Coalition, when it should have been about humanity, about history repeating itself, about the potential loss of civilian life. It should have been about a lack of strategic planning, about accountability, and about where we’ve suddenly found billions of pounds to fund a war while imposing austerity measures on Britain’s poorest.

Perhaps it’s less challenging to think about Hilary Benn’s inflections and pregnant pauses? Just as it’s easier to focus on the member of the public who shouted, “You ain’t no Muslim, bruv” to the knifeman at Leytonstone underground station, rather than on the attacker who is said to have shouted “This is for Syria”, and what such random acts of violence actually mean for Londoners. #youaintnomuslimbruv has taken on a life of its own; even David Cameron is quoting it. Like Benn’s speech, these things take on a different meaning, whether intended or not.

In a society played out on social media rather than in the real world, are we becoming conditioned to see everything in black and white, in terms of winners and heroes? Are we losing the ability to recognise nuance or irony, and when it is appropriate to clap or not?

To be fair, I don’t think Benn intended to steal the show in the House of Commons. I’ve watched footage of him over and over as he tried to sit back down on the crowded bench behind him. He didn’t high-five Angela Eagle or Tom Watson, he didn’t look jubilant or smug. He just stared at the floor, as the room – and subsequently the media – projected on to his perfectly acceptable but unexceptional speech their own more triumphant one.